“Zero means ‘nothing’“, schreef de Japanse kunstenaar Saburo Murakami in 1953, “start with nothing, completely original, no artificial meaning“. Vormt tekenen een kunstvorm in de zuiverste, meest essentiële betekenis van het woord?

Misschien meer zo nog in de periode na de Tweede Wereldoorlog, waar deze expo in het MoMA zich op toespitst. De verschrikkingen van de oorlog vergeten, alle ellende en angst achter zich laten, met een schone lei beginnen, van nul af aan. Het tekende een hele generatie. Niet verbazend dat kunstenaars uit verschillende continenten, met verschillende kunstpraktijken, enigszins tot een gemeenschappelijk, vernieuwend wereldbeeld kwamen, dezelfde materialen begonnen te gebruiken, dezelfde ideeën aan het maagdelijke papier toevertrouwden.

Het is de ambitie van deze tentoonstelling om dit aan te tonen, aan de hand van 80 tekeningen uit de eigen collectie, gemaakt tussen 1948 en 1961 door kunstenaars als Louise Bourgeois, Yayoi Kusama, Henri Matisse, Jackson Pollock, Alfredo Volpi, om er maar enkele te noemen. Voor elk van deze kunstenaars bleek het alvast de start van een fundamentele herbronning, en voor sommigen de start van een succesvolle carrière.

Ik maak hier een kleine selectie, voorzien van commentaar van de curator van de expo, Samantha Friedman. Voor een vollediger overzicht kan je steeds terecht bij het teaser-filmpje onderaan!

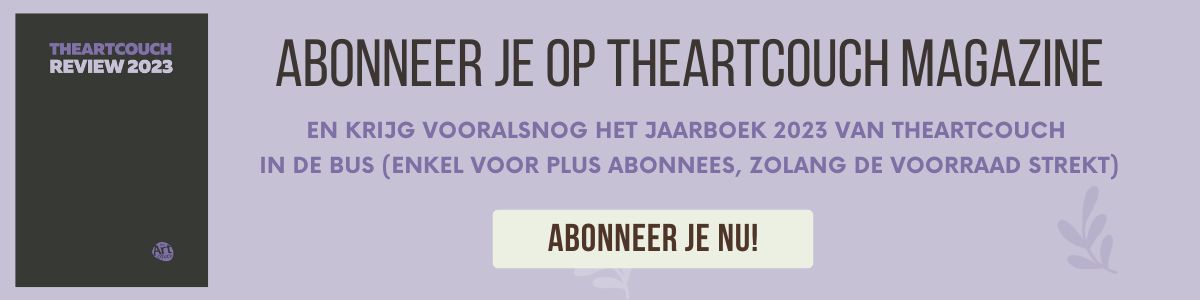

Norman Lewis. The Messenger. (1952)

In this drawing, Norman Lewis exploits two mediums to create a unique visual atmosphere, contrasting hazy passages of charcoal with precise figures in ink. “The whole thing in a sense became calligraphy,” the artist explained about the so-called “little people” motif seen here, in which “everybody was going some goddamn place and nobody was going anywhere.” (Samantha Friedman)

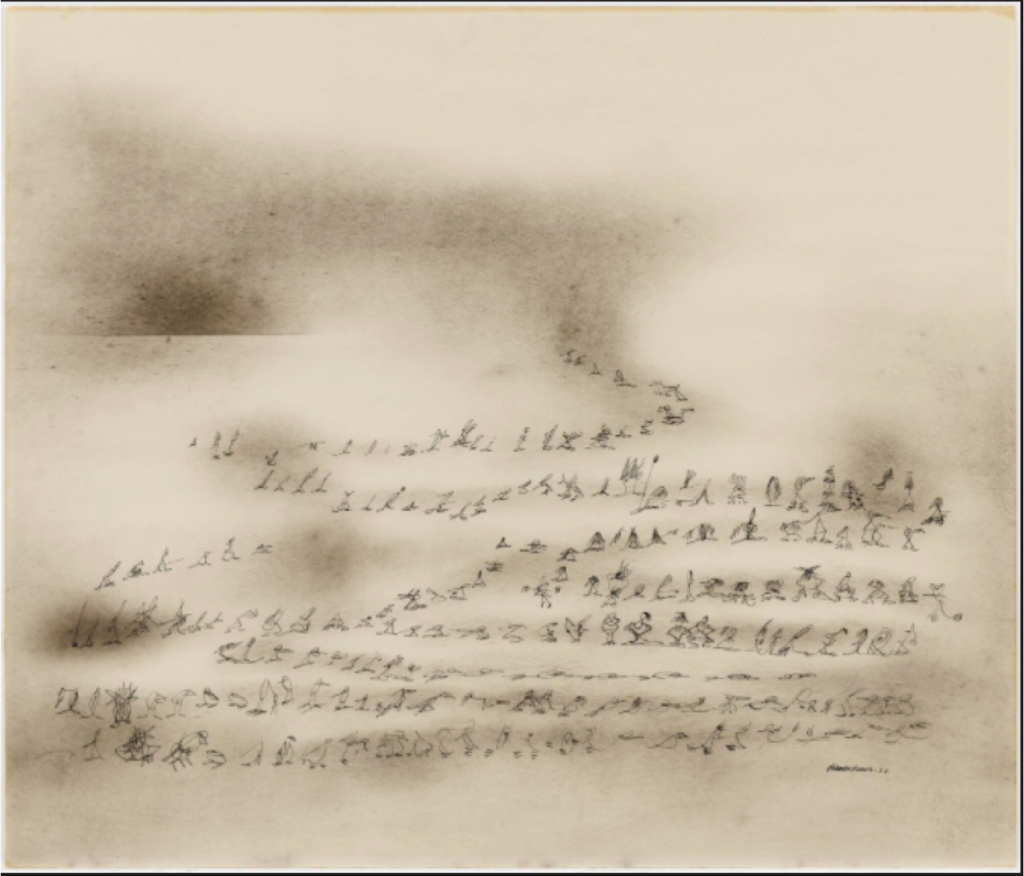

Georgia O’Keeffe. Drawing X. (1959)

In 1959 Georgia O’Keeffe took a three-month trip around the world, this drawing was inspired by the aerial views of a landscape she witnessed from a plane. “The rivers actually seem to come up and hit you in the eye,” she recalled, insisting that “there’s nothing abstract about those pictures; they are what I saw—and very realistic to me.” This approach—adopting forms from life and simplifying them toward abstraction—is similar to the one taken by the younger Ellsworth Kelly, whom O’Keeffe admired. “I’ve actually looked at one of Kelly’s pictures and thought for a moment that I’d done it,” she once said. (Samantha Friedman)

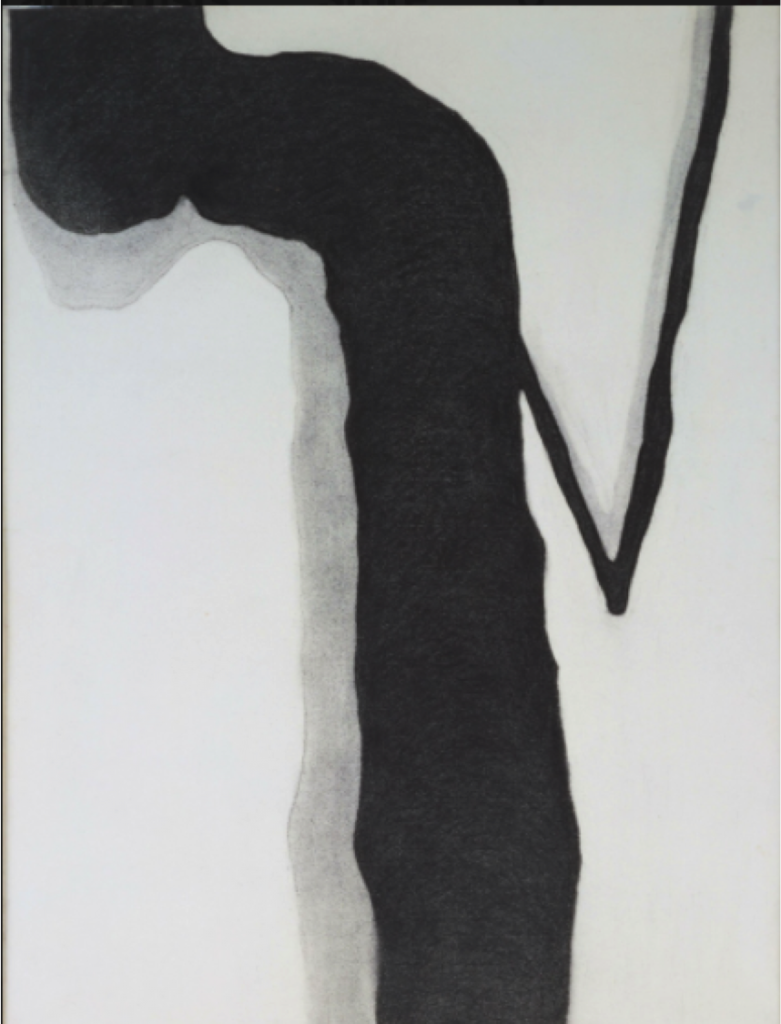

Saburo Murakami. Work Painted by Throwing a Ball (Tōkyū kaiga). 1954

One of Saburo Murakami’s Bōru, or “ball” paintings, this work’s title summarizes the action of its making: bouncing an ink-covered ball against a sheet of handmade torinoko, or “egg paper.” Though he would later become associated with Japan’s Gutai group—which emphasized the body’s materiality through performance—he made this drawing as a member of the earlier Zero-kai (Zero group). Murakami, who chose the group’s name, explained, “Zero means ‘nothing’: start with nothing, completely original, no artificial meaning.” (Samantha Friedman)

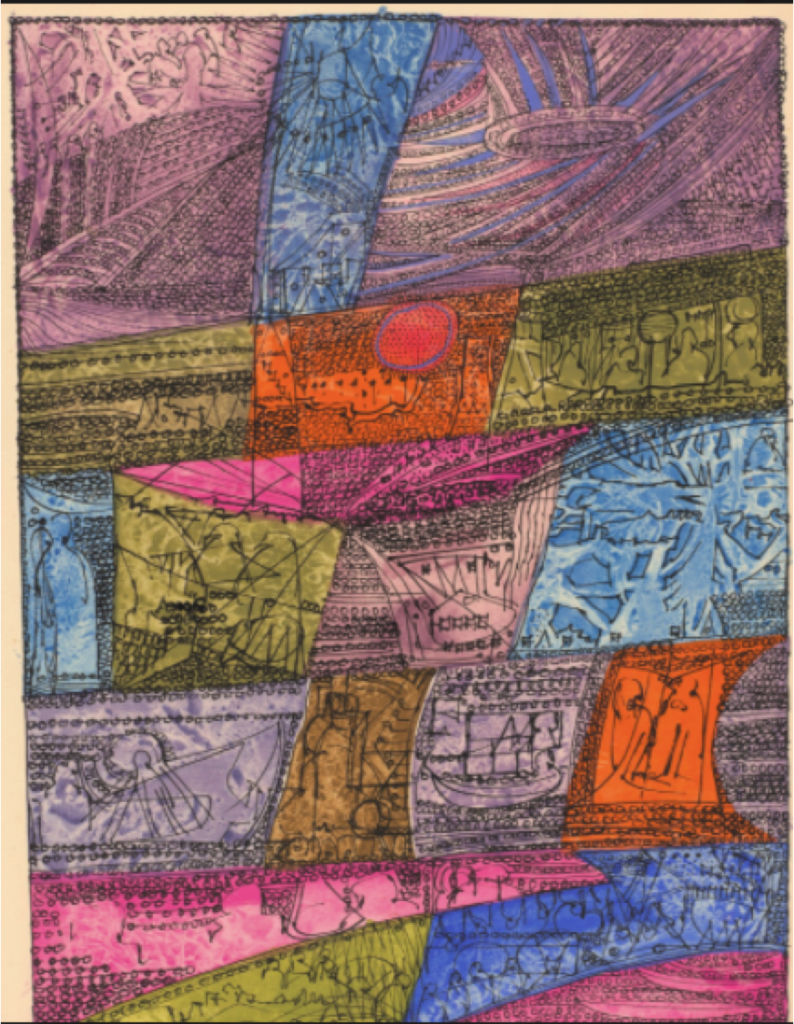

Sonja Sekula. The Voyage. (1956)

“Small size . . . suits my heart best,” Sonja Sekula wrote to her dealer Betty Parsons in 1956. “The American public must have bigness. OK. But I stick to my own need and prefer to work small scale.” The portable medium of drawing allowed the artist, who struggled with mental illness, to continue to work as she traveled back and forth between New York and her native Switzerland, where she received treatment. This transatlantic journey is alluded to in this work’s title and in the ship that appears in one of its interior frames. Together, these jewel-toned zones suggest a narrative, as one might find in the panes of a stained-glass window. (Samantha Friedman)

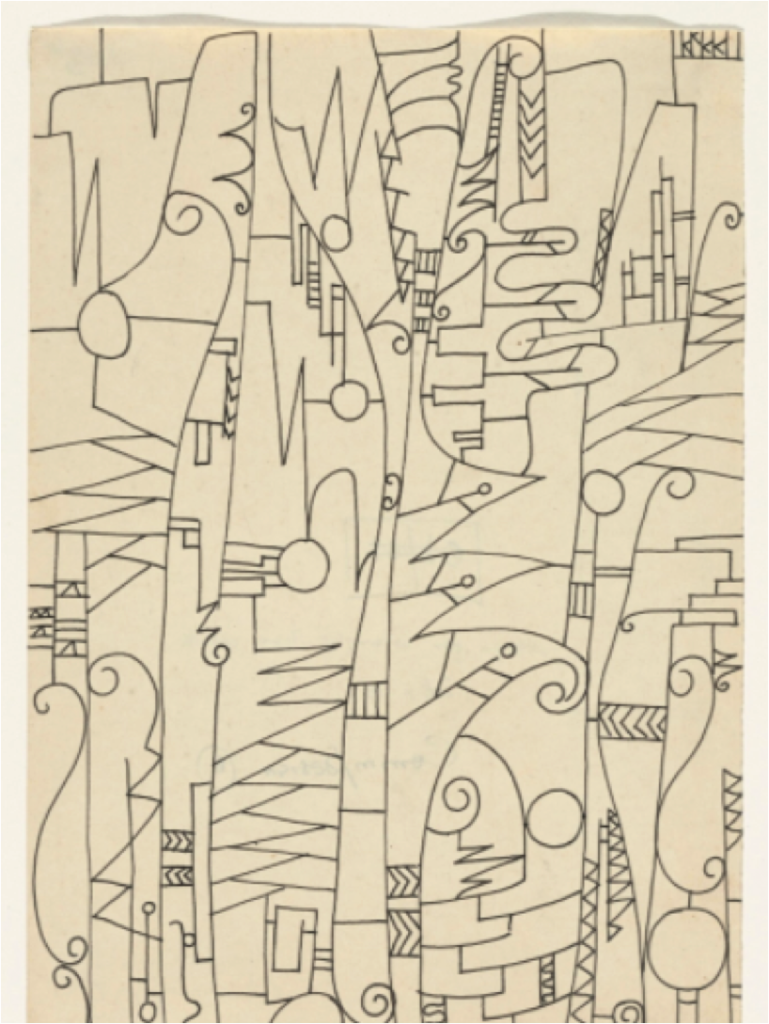

Uche Okeke. Design for Iron Work I. (1959)

“Young artists in a new nation, that is what we are!” proclaimed Uche Okeke in 1960, the year Nigeria gained independence from British colonial rule. With fellow members of the Zaria Art Society, Okeke sought to create a “truly modern African art to be cherished and appreciated for its own sake.” This drawing for ironwork adopts the lyrical curves of uli designs—traditionally practiced by the Igbo people of southern Nigeria in mural painting and body art—executing them with an imported pen and commercially produced paper instead of natural dyes. (Samantha Friedman)